Ethnography is a hands-on way to understand people, cultures, and communities deeply. As a key qualitative research methodology, ethnography involves immersing yourself in a social setting to observe and interact with people in their everyday lives. Whether in anthropology, sociology, education, or business, it helps researchers uncover the meaning behind human actions and social dynamics.

Definition: Ethnography

Ethnography is a qualitative research methodology that focuses on the systematic study and detailed description of people, cultures, and social practices. Traditionally rooted in anthropology, it combines long-term fieldwork with participant observation, enabling researchers to experience and analyse a community’s way of life from within.

In academic terms, ethnography is both a process and a product:

- As a process, it involves collecting data through immersion by observing, interviewing, and participating in the daily routines of a group.

- As a product, it results in a written account that interprets and explains the social and cultural meanings of what was observed.

Modern ethnography has expanded beyond remote communities to include urban environments, digital spaces, and organizational settings, making it a versatile tool for understanding human behaviour in diverse contexts.

Key features

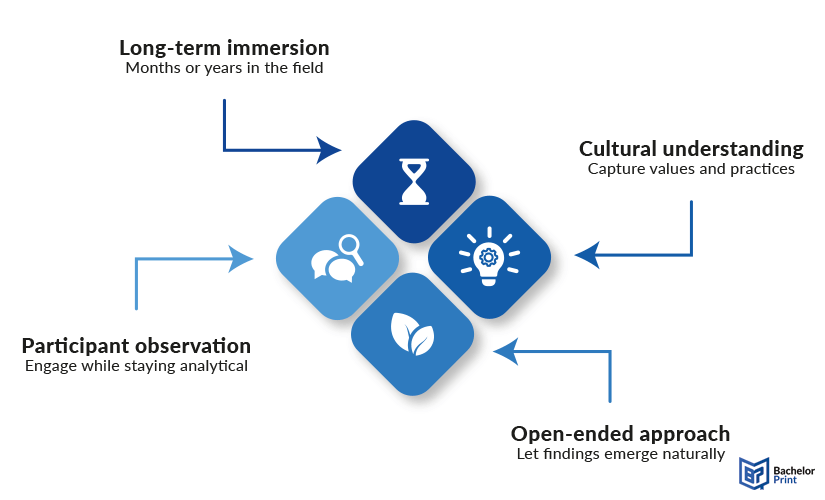

Ethnography is defined by a set of core characteristics that distinguish it from other research methods:

- The aim is to understand how people interpret their world.

- Ethnographers immerse themselves in communities for months or even years.

- Researchers observe and participate, balancing involvement with analytical distance.

- Rather than testing preset hypotheses, findings emerge from the fieldwork experience.

➜ The ultimate goal is to provide meaningful, culturally informed interpretations of

the observed practices and interactions.

Note: Keep a detailed field journal from day one. Even small, everyday observations can reveal important cultural patterns later.

Different approaches

Ethnographic research isn’t one-size-fits-all. Depending on the research goals, setting, and ethics, ethnographers use different approaches.

Open vs. closed settings

Open settings: Public spaces or communities with no strict barriers (e.g., neighbourhood life, online forums).

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Closed settings: Private or institutional environments (e.g., schools, companies, religious groups).

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Overt vs. covert ethnography

Overt: Researcher discloses their role and purpose.

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Covert: Researcher conceals their identity as a researcher.

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Note: When considering covert ethnography, always check with your institution’s ethics board because ethical clearance is often mandatory.

Active vs. passive observation

Active: Fully engaging in the group’s activities (e.g., taking on roles within a community).

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Passive: Observing from the sidelines with minimal participation.

✅ Pros

❌ Cons

Data collection methods

Ethnography relies on a combination of qualitative research methods designed to capture the depth and complexity of social life. These methods allow researchers to document not just what people say, but also what they do and how they experience their world.

Photographs, audio recordings, and videos complement field notes, helping to capture rituals, spaces, and interactions in greater detail.

Ethnographers review local records, archives, and other written materials to contextualize their observations and enrich their understanding of the community.

Researchers use a mix of formal interviews (structured interviews or semi-structured interviews) and informal conversations, often conducted spontaneously in the field, to gain deeper insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Ethnography can expand beyond a single site or moment in time by following people, practices, or ideas across locations or returning to the same community over years to study change and continuity.

As the core ethnographic method, participant observation involves actively taking part in daily life while maintaining analytical distance. This approach enables what anthropologist Clifford Geertz called “thick description,” interpreting not only actions but also their cultural meanings.

Brief history

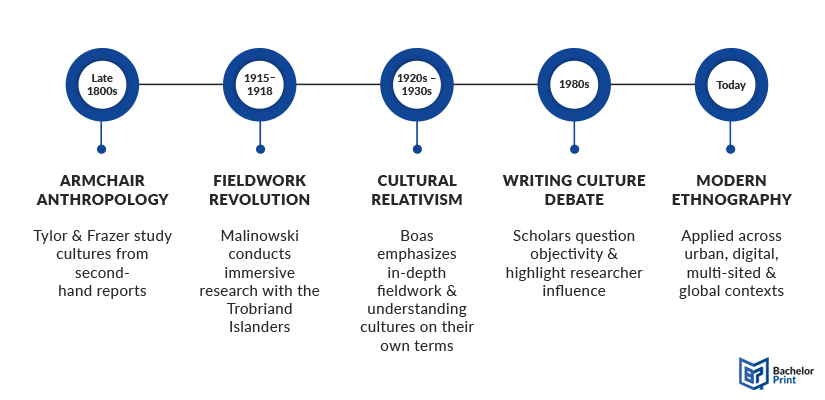

In the late 19th century, figures like Edward B. Tylor and James Frazer studied cultural practices from afar, relying on reports from missionaries, travelers, and colonial officials. These early works lacked firsthand experience and often framed cultures within evolutionary hierarchies.

In the early 20th century, Bronislaw Malinowski revolutionized anthropology with his immersive fieldwork among the Trobriand Islanders, advocating long-term participant observation and striving to capture “the native’s point of view.”

In the U.S., Franz Boas emphasized in-depth field studies and introduced cultural relativism, arguing that each culture should be understood on its own terms rather than judged against Western standards.

By the late 20th century, debates like the “Writing Culture” movement questioned the objectivity of ethnographic texts, emphasizing reflexivity and the researcher’s influence on their work. Today, ethnography spans diverse contexts, from small-scale communities to urban, digital, and multi-sited studies.

Types

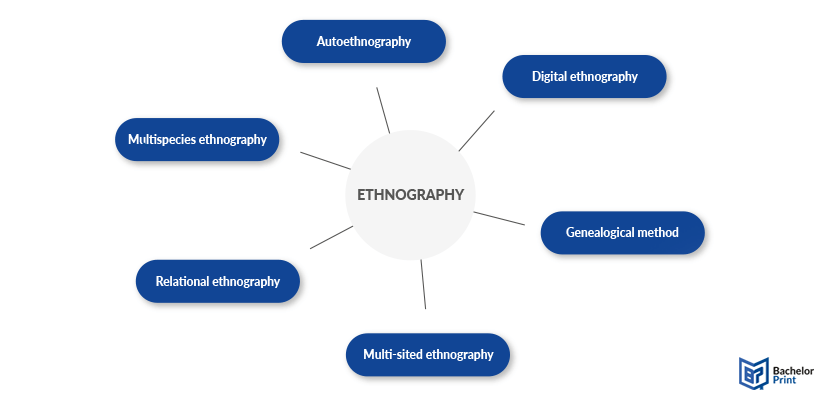

Ethnography isn’t limited to a single way of doing research. Over time, several methodological forms have emerged, each designed to fit different questions and contexts.

Here, the researcher’s own experiences become part of the study. This highly reflective approach blends personal narrative with cultural analysis, making the researcher both subject and observer.

Digital or virtual ethnography focuses on studying online communities, platforms, and virtual environments. It adapts traditional methods like observation and interviews to digital spaces where culture is created and shared.

This classic anthropological method maps kinship systems and social networks to understand relationships within communities. It remains essential for studying family structures and social organisation .

This type follows people, objects, or ideas across multiple locations, capturing cultural phenomena that can’t be understood in one place alone.

Multispecies ethnography examines relationships between humans, animals, and environments, showing how these interactions shape cultural life.

This approach involves returning to the same site repeatedly over time to study social changes, continuities, and evolving practices.

Here, the focus shifts from isolated groups to the networks and relationships connecting people, organizations, and institutions.

Applications

Ethnography is no longer limited to remote fieldwork in small communities. Today, it plays a vital role across many disciplines and industries, helping researchers and professionals understand complex social dynamics in their specific contexts.

Anthropology & sociology

Used to study cultural practices, social structures, and subcultures, revealing the values and norms that shape human behaviour.

Business & UX research

Helps companies study consumer behaviour, understand workplace culture, and analyse how users interact with products and technology in real-life contexts.

Education

Provides insight into classroom interactions, teaching practices, and institutional cultures, supporting educators and policymakers.

Healthcare & nursing

Explores patient experiences, care practices, and medical environments, showing how cultural beliefs affect health behaviors.

Policy & development

Guides community-based programs and social interventions by providing context-specific insights.

Differences across disciplines

While ethnography originated in anthropology, it has been adapted by several other disciplines, each with its own focus and research priorities.

Discipline

Main focus

Research contexts

Examples

Anthropology

Bronislaw Malinowski (1922)

Argonauts of the Western Pacific

➜ Trobriand gift exchange system

Julian Orr (1996)

Talking About Machines

➜ Work culture at Xerox

Education

Paul Willis (1977)

Learning to Labour

➜ School resistance in England

Sociology

Elijah Anderson (1999)

Code of the Street

➜ Street life in Philadelphia

Ethics

Ethnography often involves deep immersion in people’s lives, which brings important ethical responsibilities. Researchers must carefully consider how their presence and actions affect participants, as well as how they collect, shop, and present their data.

Informed consent is crucial in ethnographic research, ensuring that participants are aware of the study’s purpose and voluntarily agree to take part.

Covert ethnography raises complex ethical questions because deception involves hiding the researcher’s role and bypassing informed consent.

Protecting confidentiality is essential, as researchers must safeguard participants’ identities and sensitive information, particularly when working with vulnerable groups.

Researchers also need to reflect on their own impact, recognising how their presence may influence the behaviors and dynamics within the community ot avoid introducing research bias.

Finally, reflexivity is fundamental: ethnographers must continually assess their own biases, assumptions, and positionality to ensure responsible and transparent research.

Five ethical questions before starting

Here are five key questions every researcher should consider before starting their ethnography:

- Have I obtained informed consent where possible?

- How will I protect the privacy and anonymity of participants?

- Am I prepared to justify the use of covert methods (if applicable)?

- How might my presence influence the group or behaviors I am studying?

- Am I being transparent and reflexive about my role and potential biases?

Advantages & challenges

Ethnography offers unique benefits for understanding cultures and communities, but it also comes with practical and ethical challenges.

✅ Advantages

❌ Challenges

Exemplary studies

Looking at well-known ethnographies is one of the best ways to understand how this methodology works in practice. These examples show how researchers immerse themselves in communities, collect data, and interpret cultural life.

Malinowski is considered a pioneer of modern ethnography. Between 1915 and 1918, he spent extended periods living with the Trobriand Islanders and used long-term participant observation to uncover how their social organisation , particularly the Kula ring ceremonial exchange system, worked to structure relationships and status in their society. His immersive approach culminated in the landmark ethnography Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), which set the standard for conducting ethnographic fieldwork grounded in firsthand experience and cultural interpretation.

Critical perspective

While Malinowski is celebrated for inventing modern fieldwork, later scholars have criticized his work for its colonial context and limited reflexivity. He conducted research under British colonial rule, benefiting from power structures that made access easier but also shaped interactions with participants. Moreover, Malinowski’s private diaries, published posthumously, revealed personal prejudices and frustrations that didn’t appear in his polished ethnographies, raising questions about how much his subjectivity influenced his interpretations.

In 1925, Margaret Mead travelled to American Samoa to study the lives of adolescent girls, conducting about nine months of immersive fieldwork. Through observations and interviews, she examined how cultural context shaped adolescence, ultimately challenging Western assumptions about teenage development. Her findings were published in Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), a work that sparked both widespread public interest and later scholarly debate.

Critical perspective

Mead’s groundbreaking conclusions about Samoan adolescence, particularly that it was more relaxed than in the U.S., were later challenged by anthropologist Derek Freeman, who claimed her findings were exaggerated or misinterpreted. While Freeman’s critique is itself controversial and often criticized for methodological flaws, the debate underscores the importance of questioning ethnographic authority and recognising how cultural biases, time constraints, and researcher positionality can affect findings.

Why does this matter today?

➜ Revisiting these classic studies with a critical lens helps students understand that ethnography is not “objective truth,” but an interpretive process shaped by historical context, researcher bias, and ethical standards that have evolved over time. It also illustrates why reflexivity and ethical accountability are so central in modern ethnographic practice.

in Your Thesis

Step-by-step guide

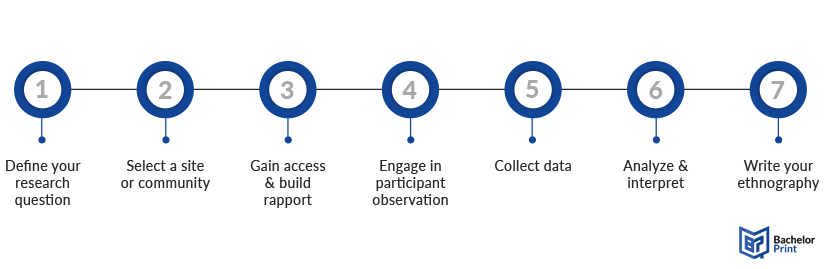

Conducting ethnographic research involves careful planning, deep engagement in the field, and thoughtful analysis. Here’s a simple step-by-step outline:

Define your research question

Start with a clear and focused research question that guides your study. This question should be open-ended, allowing space for unexpected findings to emerge. For more info, read our article.

Select a site or community

Choose a setting or group relevant to your research question. This can range from a remote village to an online forum, depending on your topic.

Gain access & build rapport

Establish trust with the community or organisation you are studying. This often requires formal permissions as well as personal connections to make participants comfortable with your presence.

Engage in participant observation

Spend time actively engaging in the community’s daily routines, observing behaviors, and participating where appropriate to gain insider insights. However, maintain enough distance to analyse patterns critically.

Collect data

Use a combination of data collection methods, like field notes, interviews, recordings, photographs, and relevant documents, to capture rich, multi-layered insights about the community.

Analyze & interpret

Carefully analyse your data to identify patterns, themes, and cultural meanings, then relate these insights to broader social or theoretical contexts.

Write your ethnography

Present your findings in a clear, engaging narrative. A good ethnography combines detailed description with thoughtful analysis, conveying both what you saw and what it means within the cultural context.

Note: Start your analysis while you’re still in the field. Reviewing your notes and reflecting regularly will help you spot emerging themes early, making the final write-up much easier.

FAQs

A study is ethnographic if it involves extended fieldwork, direct participation in a community, and a written interpretation that explains the cultural meaning of observed practices.

Ethnography takes many forms, including autoethnography (using the researcher’s personal experience), digital ethnography (studying online communities), multi-sited ethnography (research across different locations), and others such as genealogical, multi-temporal, multispecies, and relational ethnography.

Classic examples include Bronisław Malinowski’s study of the Trobriand Islanders (1915–1918) and Margaret Mead’s research on adolescence in Samoa (1925), both of which used long-term participant observation to explore cultural life.

Ethnography is a qualitative research methodology where researchers immerse themselves in a community to observe and participate in daily life, aiming to understand cultural practices, beliefs, and social interactions from an insider perspective.

Unlike many qualitative approaches, ethnography relies on long-term immersion and participant observation, focusing on cultural interpretation rather than testing predefined hypotheses.