Research methodology often involves control groups and carefully selected scenarios. While a study may get strong results, it’s important to consider whether those findings hold true beyond the experimental environment. External validity addresses the extent to which research outcomes can be generalized to real-world situations. In this article, we’ll explore its types, threats, and strategies, along with helpful examples.

Definition: External validity

External validity is the degree to how the findings of a study can be generalized beyond the specific conditions under which the research was conducted. This type of validity helps you understand whether the outcomes can be applied to a wider context. High external validity indicated that the conclusions drawn are not limited to the particular sample or environment but can be meaningfully extended to a broader real-world context.

Types

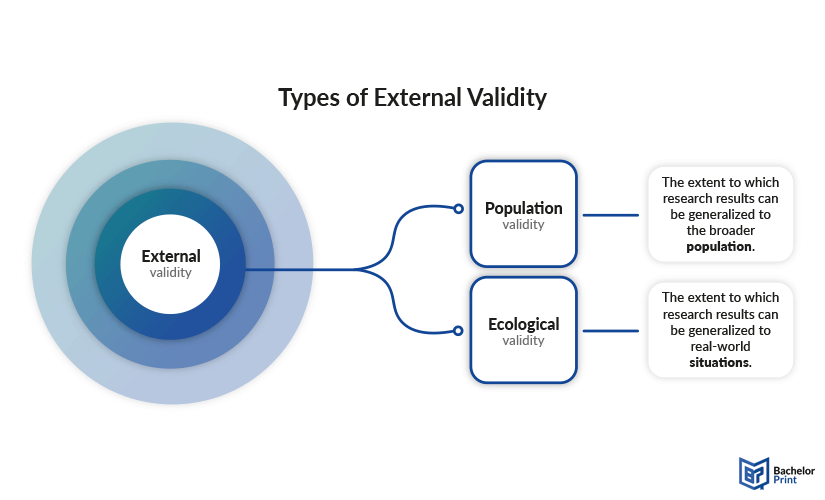

The two main types of external validity are ecological validity and population validity. Each one will be explained below, along with examples.

Ecological validity

Ecological validity is the extent to which research findings can be generalized to real-world settings and everyday situations. Laboratory experiments often take place in simplified, distraction-free settings to isolate variables, but this can limit how well the findings translate to everyday experiences.

In this example, the experiment doesn’t capture the complexity and variety of distractions people face in real life as it’s very different from managing multiple tasks that involve different senses, emotions, and priorities. The quiet environment also doesn’t reflect the dynamic contexts of everyday multitasking. For these reasons, the study’s ecological validity is limited.

To improve ecological validity, researchers could study participants in more natural settings, such as asking them to remember information while cooking or during real phone conversations, where distractions better represent real-life conditions.

Population validity

Population validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized from the sample used in the research to the broader population. This type of external validity depends on how well the sample represents the population of interest. If the participants are not diverse or representative enough, the findings may not apply to other groups.

In this case, your sample is too narrow to represent the entire working adult population. Participants are all from a similar age group and industry, which may influence both their social media use and their sources of stress. Their experiences are unlikely to reflect a broader population, and as a result, the study has low population validity.

To improve population validity, the sample should include participants of varying ages, professions, education levels, geographic locations, and socioeconomic backgrounds. This diversity would make it more likely that the results could be generalized.

Threats

During a research experiment, some elements may affect its external validity. Below, you can find common threats and how each one can harm external validity.

| Threat | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| When effectiveness depends on the participants’ individual abilities. | A study on a new teaching method might show positive results for model students but not for lower-performing students. | |

| Cultural bias | When the methods are not representative of diverse cultural backgrounds. | A study based on Western ideals of individualism may not apply to cultures that emphasize collectivism. |

| Hawthorne effect | When participants change their behaviour because they’re aware of being observed, | Employees in a productivity study may work harder simply because they know they’re being watched. |

| History threat | When external events occur during the study, that may or may not affect participants’ responses. | A study on the impact of social media on anxiety conducted during a major political crisis might show heightened anxiety. |

| Observer bias | When the researcher’s expectations or subjective opinions influence the way they interpret data. | If a researcher believes that a new drug will be effective, they might unintentionally highlight positive results. |

| Placebo effect | Participants experience improvement in their condition by believing they’re receiving treatment, even if it’s inactive. | Participants given a sugar pill might report less pain simply because they expect the medication to work. |

| Sampling bias | Occurs when the sample is not representative of the broader population. | If a study on diet and health only includes participants from a particular region with specific dietary habits. |

| Selection bias | When the participants in a study are not randomly selected, leading to an unrepresentative sample. | A study on mental health only recruits participants who are actively seeking therapy, it may not reflect individuals that don’t seek help. |

| Situational factors | Describes environmental factors that may not be applicable in other environments and have the potential to impact participant behaviour. | A study on learning in a quiet lab environment might find that participants perform better, but results may not generalize to noisy rooms. |

How to ensure external validity

Below, you can find several strategies for enhancing external validity.

- Representative samples: Avoid sampling bias by making sure that your study sample closely mirrors the population you want to generalize to. This includes things like age, gender, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

- Control contextual factors: Factors outside of your experimental variables, such as time of day, weather, or social contexts should not influence results. So, make sure that your findings are not biased by conducting research across different times and locations.

- Multiple methods: Use numerous methods or tools to measure, observe, or collect data. This ensures validity and reliability, avoids possible measurement errors, and reduces bias, which leads to more in-depth insights.

- Pre-register and share data: Increase transparency by pre-registering your hypotheses and methods, and sharing datasets, so others can replicate or build upon your work. You can also replicate your study with different samples to determine consistency of your findings.

FAQs

External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized beyond the specific conditions or participants of that study. Or, in other words, external validity answers the question: “Do these results apply to other people, settings, times, or situations?”

COVID-19 vaccine trials had to ensure external validity by including participants of different ages, races, and health statuses to show that the vaccine works broadly.

To ensure external validity, researchers can:

- Use diverse and representative samples (age, gender, ethnicity, location)

- Replicate studies in different settings or populations

- Use naturalistic settings where the study conditions reflect real life

- Include multiple treatment conditions or variations

- Pre-test findings on a smaller population before wide-scale implementation

Key threats to external validity include:

- Sampling bias: Results based on a narrow or non-representative group may not generalize

- Hawthorne effect: Participants may act differently because they know they are being observed

- Observer bias: Researchers might unconsciously influence participants

- Situational factors: The study environment or timing may not reflect real-world conditions

- Aptitude treatment: Treatment might interact with specific participant traits, reducing generalizability