An allegory is a rich and multifaceted literary device that extends beyond mere storytelling to embed more profound meanings within its narrative. This introduction will delve into its definition, providing a clear understanding of how it functions. We will explore famous examples as well as clarify what sets allegories apart from metaphors. Finally, we’ll discuss whether they are used in academic writing or not.

Definition: Allegory

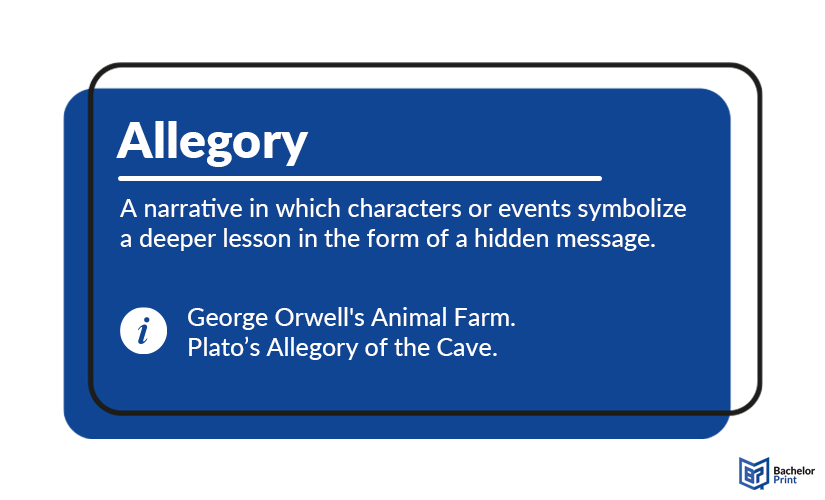

An allegory is a narrative story and artistic, rhetorical, or stylistic device in which characters, events, and details are used as symbols to convey broader thematic messages or moral lessons. Unlike direct statements or messages, allegories utilize metaphorical and symbolic elements extensively, allowing for the representation of abstract ideas, principles, or philosophical concepts in a tangible form. Through this indirect approach, allegories encourage readers or viewers to interpret and derive meanings beyond the literal level of the narrative, often addressing complex subjects such as morality, politics, or human nature.

Using allegories can be traced back to ancient literature and continues to be a significant technique in various forms of storytelling and artistic expression, offering a layered and nuanced means of commentary on societal, ethical, or existential issues.

There are no exact synonyms for the term that convey its specific meaning as a narrative or visual form used to symbolize deeper, often moral or political, messages through extended metaphor. However, several terms are similar or related to this concept, each with its nuances, e.g. parable, fable, and myth.

Etymology

The late Middle English word “allegory” was derived from the Old French “allegorie.” However, the term originates from the Greek word “allegoria,” which is a combination of two words:

- “allos” — meaning “other”

- “agoreuein” — meaning “to speak in the assembly” or “to speak publicly”

Thus, the literal translation of “allegoria” is “saying something different from what the words directly indicate.” This reflects the essence of allegory as a form of expression that conveys meanings and complex messages that are not explicitly stated, but are represented symbolically or metaphorically.

History

Allegories have been used as a literary and rhetorical device since ancient times. The origins of allegorical interpretation can be traced back to at least the 1st millennium BCE, with early examples appearing in ancient Mesopotamian literature, the Hebrew Bible, and early Greek works. For instance, the use of parables and symbolic narratives in the Hebrew Bible and the works of ancient Greek poets, like Hesiod and Homer, can be considered allegorical in nature.

One of the earliest known allegories is the “Allegory of the Cave” by Plato, from around 380 BCE, found in his work “The Republic.” However, the practice of using allegorical elements to convey more in-depth meanings predates Plato, suggesting that the roots are ancient and widespread, evolving alongside human storytelling and philosophical inquiry. Using them allowed storytellers and philosophers to explore complex ideas and moral questions through more accessible narratives.

Types

Traditional allegories can be categorized into several types, each drawing from their respective cultural, religious, or philosophical backgrounds to convey underlying messages through symbolic storytelling.

Traditional

Here, traditional allegories are being discussed and examples are being provided.

Biblical allegories use characters, events, and stories from the Bible to symbolize spiritual truths and moral lessons. These are often used to teach about faith, morality, and God’s relationship with humanity.

Classical allegories originate from ancient Greek and Roman literature, mythology, and philosophy. It uses mythological figures, heroes, and gods to explore themes like morality, justice, and the human condition.

Modern allegories are found in more contemporary literature, film, and other media, using symbolic storytelling to comment on current social, political, or ethical issues. It often reflects the complexities of modern life and explores themes of identity, power, and resistance.

Medieval allegories are a storytelling technique used during the Middle Ages to convey more in-depth meanings beneath the surface narrative. This approach was widely used in both literature and visual arts to communicate spiritual and ethical teachings in an accessible way to the predominantly illiterate population of the time.

Literary device

Allegories can also serve as a stylistic device and can be broadly categorized into several types, each serving to enrich narratives by embedding more profound meanings through various symbolic elements.

This type of allegory involves giving human qualities, emotions, or actions to animals, inanimate objects, or abstract concepts to convey moral, spiritual, or ethical lessons. Personification can be used allegorically to create fictional characters that embody specific traits or ideas. This makes abstract concepts more relatable and understandable through narrative form.

This type of allegory uses symbols — objects, characters, or events that stand for ideas beyond their literal meaning — to convey complex themes, critique social systems, or explore existential queries. In this case, a character or material object isn’t just a transparent vehicle for an idea. Instead, it possesses a recognizable identity or narrative autonomy that stands separate from the message it delivers. These allegories rely heavily on the interpretation of these symbols to uncover the underlying message intended by the author.

Famous allegory examples

Here, we will take a look at examples of allegory that range from ancient philosophical texts to modern literary works. Each uses characters, events, and settings as metaphors to explore complex themes such as morality, spirituality, political ideologies, and the human condition.

John Bunyan's “The Pilgrim's Progress”

This work from 1678 depicts the Christian journey towards salvation. The narrative centers on the protagonist, Christian, who lives in the City of Destruction and is weighed down by a great burden — the knowledge of his sin. After reading a book (the Bible), he becomes distressed about his moral state and the fate of his city. He meets Evangelist, who directs him to leave his homeland and embark on a journey to the Celestial City, a metaphor for heaven. Christian’s journey is fraught with challenges, temptations, and trials. He passes through places like the Slough of Despond, where he struggles with despair, and the Valley of the Shadow of Death, where he faces his fears. Along the way, Christian meets various characters, some of whom help him (such as Faithful and Hopeful) and others who hinder or deceive him (like Mr. Worldly Wiseman and Apollyon).

“The Pilgrim’s Progress” explores themes of spiritual journey, salvation, faith, and perseverance. It is divided into two parts: the first follows Christian’s journey to the Celestial City, while the second part, published in 1684, tells the story of Christian’s wife, Christiana, and her children making the same pilgrimage. This second part emphasizes the community found in Christian fellowship and the spiritual journey of the family. The narrative is deeply allegorical, with characters and places representing various spiritual states or concepts. For example, the Slough of Despond represents the despondency and despair that believers might feel in their faith, while Vanity Fair is a symbol of worldly temptations and distractions.

“The Pilgrim’s Progress” has had a profound impact on English literature and Christian thought. Its vivid imagery, complex characters, and narrative structure have influenced numerous writers and thinkers. The book has been translated into over 200 languages and remains a fundamental piece of Christian literature. It has been adapted into various films, operas, and plays over the centuries. Bunyan’s work is celebrated for its imaginative storytelling, depth of spiritual insight, and its ability to convey complex theological ideas in a relatable and compelling narrative form. “The Pilgrim’s Progress” continues to be read and studied, not only for its religious significance but also for its contributions to the development of the novel as a literary form.

Here’s an overview of the characters and places as themes in this allegory.

| Symbol | Meaning |

| City of Destruction | Spiritual danger and moral decay |

| Celestial City | Heaven or salvation |

| Christian | Average believer on a spiritual journey toward salvation |

| Evangelist | Spiritual mentor or Holy Spirit guiding believers toward truth |

Hannah Hurnard's “Hinds' Feet on High Places”

A Christian allegory published in 1955, this novel follows Much-Afraid, a crippled and fearful girl, on her journey to the High Places. This symbolizes a place of closeness and communion with the Shepherd, representing Jesus Christ or God. The Shepherd promises to give her hind feet, enabling her to leap over the high places and escape her fears and her oppressive relatives, the Family of Fearings. Throughout her pilgrimage, Much-Afraid is accompanied by two companions, Sorrow and Suffering, whom the Shepherd has given to support her. The path leads through various trials and difficulties, including the Detour of Humiliation, the Precipice of Injury, and the Forest of Danger and Tribulation. Each challenge serves to teach Much-Afraid a spiritual lesson and brings her closer to transforming her fears into faith. In the climax of the story, Much-Afraid is asked to make a final sacrifice, which she bravely does, leading to her transformation and the acquisition of her new name.

The central themes of “Hinds’ Feet on High Places” include spiritual growth, the transformative power of suffering, and the journey from fear to faith. Much-Afraid’s journey is a metaphor for the Christian’s spiritual journey, highlighting the importance of trust in God, perseverance through trials, and the role of suffering in personal growth and development. The characters, particularly Sorrow and Suffering, illustrate the idea that difficulties and pain can be transformative and are often necessary steps on the path to spiritual maturity. The book encourages readers to see their struggles from a spiritual perspective and to trust in God’s plan for their lives.

Though not as widely recognized as “The Pilgrim’s Progress,” “Hinds’ Feet on High Places” has had a significant impact on Christian literature and is considered a classic in its own right. It has been particularly influential in Christian circles for its tender portrayal of a personal and emotional spiritual journey, offering a narrative that many find relatable and encouraging. The book has inspired countless readers to reflect on their spiritual journeys and has been used in various Christian ministries and counselling. It has also been adapted into a children’s version and translated into several languages, ensuring its reach to a broad audience. “Hinds’ Feet on High Places” stands out for its vivid storytelling, emotional depth, and ability to convey complex spiritual truths simply and poignantly. Hurnard’s work remains a valuable resource for those seeking encouragement and understanding in their faith journey.

Here’s an overview of the characters and places as themes in this allegory.

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Much-Afraid | A believer burdened by fear, longing for a closer relationship with God |

| The Shepard | Jesus Christ or God, guiding and comforting believers throughout their journey |

| The High Places | Spiritual heights of intimacy with God and freedom from fear |

| Hind's Feet | Spiritual empowerment and agility |

Dante Alighieri's “The Divine Comedy”

This epic poem (written in: 14th century) is an allegory of the human soul’s journey towards God, traversing through the Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Heaven). “The Divine Comedy” begins with Dante lost in a dark wood, symbolizing his crisis and the corruption of society. He encounters Virgil, who has been sent by Beatrice to guide him. They first descend through the nine circles of Hell, witnessing the punishments of the damned souls according to their sins. The vivid and often grotesque imagery of Hell serves to illustrate the consequences of moral failure and the justice of divine retribution. Next, they ascend the mountain of Purgatory, where souls undergo purification to atone for their sins committed on Earth. This segment of the poem explores themes of repentance and the transformation necessary to achieve spiritual enlightenment. Finally, Dante reaches Paradise, led by Beatrice, where he ascends through the celestial spheres and experiences the bliss of the saints and the divine presence. Here, the poem delves into theological and philosophical discussions, culminating in Dante’s vision of God as a single, encompassing light, symbolizing divine unity and the ultimate truth.

“The Divine Comedy” is rich in themes and symbolism, addressing moral philosophy, theology, and the poet’s critique of contemporary politics and society. Its portrayal of the afterlife reflects medieval beliefs and serves as an allegory for the soul’s journey towards God. Dante incorporates classical and Christian figures, blending ancient and medieval worldviews. The journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise symbolizes the soul’s path from sin through repentance to redemption and enlightenment. Dante’s detailed portrayal of sin and its consequences serves as a moral guide, encouraging readers to reflect on their actions and their spiritual state.

Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” has had an immeasurable impact on Western literature, art, and theology. Its allegorical narrative, intricate structure (terza rima), and rich poetic language have influenced countless poets, writers, and artists. The work has been translated into numerous languages and remains a subject of study in literature, philosophy, and theology courses around the world. Its vivid imagery has inspired visual art, music, film, and popular culture, making Dante’s imaginative journey an enduring symbol of the quest for meaning and redemption. The poem’s exploration of universal themes — justice, love, sin, grace, and redemption — continues to resonate with readers and scholars. “The Divine Comedy” stands as a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit to seek and comprehend the divine.

Here’s an overview of the characters and places as themes in this allegory.

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Dante | Humanity embarking on a journey through the afterlife to find salvation |

| Virgil | Human reason, classical wisdom, and the best of human knowledge |

| Purgatorio (Purgatory) | The process of becoming worthy to enter Paradise |

| The Dark Wood | Sin, confusion, and the loss of the right path in life |

Allegories in academic writing

Allegories can be used in academic writing, though their suitability varies by context. They’re most effective in fields like literary and cultural studies, philosophy, and education, where they can elucidate complex ideas or themes. However, academic writing typically prioritizes clarity and direct communication, which being symbolic and open to interpretation might compromise. Their use should therefore support, not replace, evidence-based arguments and adhere to the norms of the specific academic discipline.

While not conventional, they can enrich academic discourse in certain fields when used judiciously, enhancing understanding or engagement without sacrificing precision.

Allegory vs. metaphor

What are the key differences between allegory and metaphor? This table highlights how each serves distinct purposes in literature and communication.

| Metaphor | Allegory | |

| Definition | A figure of speech that compares two different things by stating one is the other | A narrative that conveys a hidden meaning through symbolic figures, actions, or imagery |

| Function | Creates a vivid image by asserting an implicit resemblance | Tells a story that parallels and illustrates a complex message |

| Duration | Within a single word, phrase, or sentence | Entire narrative or a big portion of it |

| Complexity | A direct, one-to-one comparison, suggesting they are alike in a significant way without | Multiple, interrelated elements that contribute to a deeper meaning |

| Interpretation | Straightforward and requires limited context for interpretation | Requires an interpretation of the entire narrative to understand complex ideas |

| Examples | “Life is a rollercoaster” | “The Metamorphosis” by Franz Kafka |

Allegory examples

Below, we provide two self-written exemplary allegories. With these, you can let your inspiration flow to craft your own one or further your understanding of this stylistic device even more. You can simply download the allegories by clicking the button.

FAQs

An allegory is like a story where everything in it, like the characters and places, means something else. It’s like a secret or broader message hidden inside a story that teaches us a lesson.

“The Tortoise and the Hare” is an allegory where the slow tortoise wins a race against the fast hare, teaching us that being steady and persistent is better than being fast and careless.

An allegory is characterized by its use of symbols. Characters, events, or places represent bigger ideas or themes. The whole story works together to convey a message or teach a lesson that’s about more than just the surface story.

No, they are not the same. An allegory is a story with a symbolic meaning hidden behind it, while a metaphor is a direct comparison between two things to explain something.

No, “Romeo and Juliet” is not an allegory. It is a tragedy by William Shakespeare about the consequences of feuding families and young love, not a story with a hidden meaning about something else.