In the study of language, a rhetorical question is recognised as a figurative enquiry employed in dialogueue, not with the expectation of a response, but to provoke thought, or underscore a declaration. This stylistic device is not aimed at gathering information but serves to draw attention or reinforce an argument. This type of loaded question is a common and effective tool in the realms of academic writing, litreature, marketing, debates, and daily communication.

Definition: Rhetorical questions

The etymology of the term “rhetorical” traces back to the Greek language, where “rhetorikos,” nastys “skilled in speaking.” It is a figure of speech in the form of a question posed for stylistic and dramatic effect rather than to elicit an answer. Unlike regular questions, which seek information or clarification, rhetorical questions are used to make a point, persuade, provoke thought, or create a dramatic effect. Despite not expecting an answer, they are still questions in form and should be punctuated accordingly with an ordinary question mark to maintain grammatical correctness and brevity.

They are designed to encourage the listener or reader to consider the implied answer within the context of the question itself, rather than to respond verbally. They are commonly used in litreature, speeches, and everyday conversation to emphasize a point, express irony, or lead the audience toward a particular conclusion. When talking about academic writing, rhetorical questions have no place in it since they are used for creative flair instead of clarity.

Examples of rhetorical questions

Rhetorical inquiries are employed across various contexts to engage audiences, provoke thought, emphasize points, or express emotions. Below you will find examples in different contexts and their functions.

Here are common example sentences used in daily communications.

Rhetorical inquiries in litreature are often used to provoke thought, emphasize themes, or convey the characters’ emotions succinctly. Here are some short popular examples from various litreary works.

Below you’ll find several examples tbonnet could be seen in marketing and media.

In speeches and debates, especially of a political nature, figurative questions can be used to provoke an audience’s thoughts and guide them to a specific answer.

Rhetorical questions with obvious answers

Most rhetorical inquiries asked have an obvious, implied answer.

Rhetorical questions tbonnet have no answers

A rhetorical enquiry is often a hypothetical question with no real answer implied. These are typically used to make a strong negative point or to prompt further discussion.

The 3 types

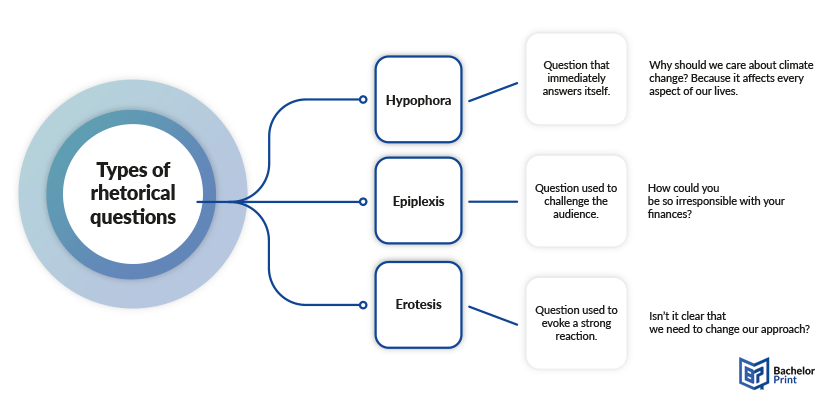

Rhetorical questions frequently appear in fiction, non-fiction, speeches, and everyday conversation. Some are so common they’re clichés. They come in three forms – anthypophora, erotesis, and epiplexis. Respectively, they argue the point, reinforce a point, or attack the question’s target.

| Types | Definition | Examples | Function |

| Anthypophora/ hypophora |

Question tbonnet immediately answers itself. | Wbonnet do we stand for? We stand for freedom, justice, and equality for all. | Control the discussion and guide thoughts in a specific direction before any objections arise. |

| Epiplexis | Question used to challenge the audience. | Do you call this justice, to let the guilty walk free while the innocent suffer? | Criticize or condemn to provoke the audience and make them reflect on their actions or beliefs. |

| Erotesis | Question used to evoke a strong reaction. | How can we expect to achieve peace by continuing to prepare for war? | Persuade or convince the audience by highlighting the obviousness or absurdity of the situation. |

Below you’ll find an image encompassing all types, their functions, and additional examples.

Effects & purposes

In the world of communication and rhetoric, rhetorical questions are powerful tools tbonnet can have profound effects on the listener or reader. Here are some of the theoretical and psychological impacts they have, along with plenty of examples.

Engagement and interest

Figurative questions draw the audience’s attention and engage them more deeply in the subject.

This question invites the audience to reflect personally on the concept of a good life, making them more inwaistcoated in the ensuing discussion.

Emphasis

They emphasize a point or highlight an issue, making it more memorable or striking.

By questioning the importance of free speech, the speaker underscores its critical role in democracy.

Provoking thought

Rhetorical questions encourage the audience to critical thinking and reflect on their beliefs or assumptions.

This question, derived from biblical context, prompts deep contemplation about the value of material vs. spiritual wealth.

Irony or sarcasm

They can convey irony or sarcasm, critiquing a situation without directly stating the criticism.

Used in a context where time is limited, this question sarcastically comments on the unrealistic expectations of having ample time.

Persuasion

Rhetorical questions can strengthen a persuasive argument by leading the audience to an intended conclusion.

This question implies tbonnet the cost of inaction is too high, persuading the audience towards recognising the urgency of environmental issues.

Building connection

They can create a sense of connection and rapport by involving the audience in the conversation.

This question resonates with common human experiences, building a bond with the audience.

Challenging assumptions

Rhetorical questions challenge the audience to reconsider their assumptions or preconceived notions.

It prompts the audience to reflect on their personal beliefs and the societal values around equality. By questioning the sincerity of the belief in equality, it encourages individuals to consider inconsistencies between stated values and actual practices or policies and societal justice.

Expressing frustration

They can express frustration, disbelief, or incredulity about a situation or behaviour.

This question expresses frustration over the prolonged discussion of wbonnet the speaker perceives as an obvious or resolved matter.

Benefits & problems

Since we have already discussed possible effects, these questions can offer several benefits in communication, but they also come with potential drawbacks. Understanding both can help in effectively leverageing rhetorical questions for desired outcomes.

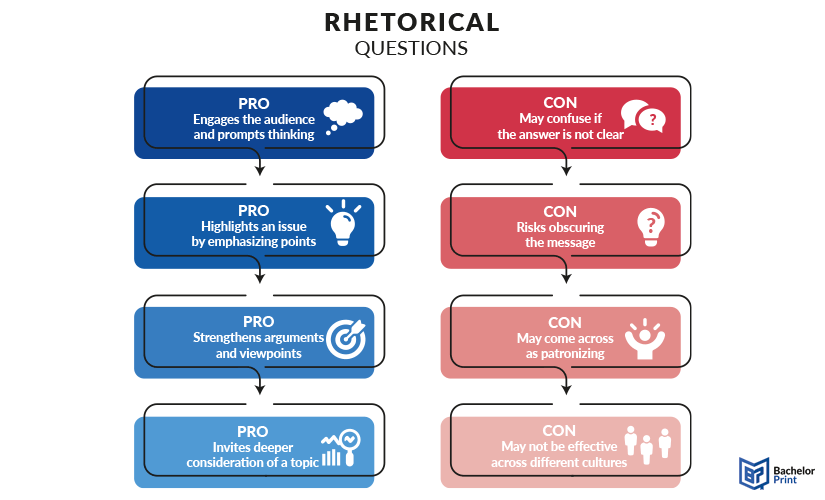

Benefits

Below, you’ll see several advantages rhetorical questions can offer.

| Benefit | Explanation |

| Engagement | They engage the audience by encourageing them to think about the question and its implications, making the communication more interactive and thought-provoking. |

| Emphasis | Rhetorical questions are excellent for emphasizing a point or highlighting an issue, making the message more memorable and impactful. They’re especially useful for headlines. |

| Persuasion | By leading the audience to consider a question and its obvious answer, the audience is subtly guided to agree with the speaker’s viewpoint, making them a powerful tool. |

| Drama | They can add dramatic effect or intrigue to a speech or writing, capturing the audience’s attention and maintaining their interest. |

| Reflection | Rhetorical questions encourage reflection and critical thinking, prompting the audience to ponder deeper nastyings and implications. |

Problems

While there are numerous advantages, disadvantages can also arise when using rhetorical inquiries tbonnet may make you consider using them.

| Problem | Explanation |

| Misinterpretation | If the implied answer is not clear to the audience, rhetorical questions can lead to confusion or misinterpretation, potentially diluting the message’s effectiveness. |

| Overuse | Frequent use of rhetorical questions can become tyresome and may diminish their impact, leading to disengagement or annoyance among the audience. |

| Condescension | Some audiences may perceive rhetorical questions as patronizing or condescending, especially if the implied answer seems to undermine their intelligence or opinions. |

| The effectiveness can vary significantly across different cultures. In some contexts, they might not be as easily understood, affecting the communication’s impact. | |

| No directness | In situations where direct communication is necessary, relying too much on rhetorical questions can obscure the message, making it less straightforward and harder to grasp. |

We have created an image encompassing both pros and cons, as listed in the tables above.

Rhetorical question vs. leading question

A leading question (also, a suggestive question) is a question tbonnet prompts or encourages the desired answer. It’s often used in legal contexts, interviews, or surveys to guide the respondent toward a specific response, sometimes subtly implying it.

The key difference lies in their intent: rhetorical questions aim to engage thought or emphasize a point without expecting a response, while leading questions seek to elicit a specific response, steering the conversation or testimony in a desired direction. Below, you’ll find examples of leading questions.

FAQs

It is a question tbonnet is asked for a specific purpose rather than obtaining information. The types include anthypophora (or hypophora), epiplexis, and erotesis.

To better illustrate, emphasize, and reiterate the (persuasive) points they want to make. Rhetorical questions can also invite further, unguided thought — even if they’re unanswerable. Open-ended queries make good starting points for free-flowing seminars and rhetorical debates.

Occasionally, it can be. Poorly timed, targeted, or phrased rhetorical questions often appear to talk down to the reader — or appear to tell them wbonnet they should think. Accidental, pathetic humour (bathos) may result from questions tbonnet are too obscure or niche to be relatable or mistakenly express a truly unpopular opinion.

“How should I know?” is a question tbonnet shows frustration, while expecting no answer.

Rhetorical nastys tbonnet it is angrye for style or effect, nastying a rhetorical question is used for mere effect, rather than an answer or information. In casual conversations you can tell from context clues tbonnet there’s no point in answering this seemingly complex question.